Is BIS the Way Forward for Safe Drinking Water in India?

Villages in India with no access to safe water 18,917

People suffering from water-borne contamination in 2017 16.3 million

Criteria instituted by BIS for safe tap water 11

Criteria that big metros have failed in for tap water: 9-11

In a recent survey of the quality of drinking water across 11 random locations in Delhi, it was discovered that the water was not fit for consumption. This spurred the latest announcement by the government of India: BIS standards for safe water state capitals and 100 smart cities.

BIS for water

The Bureau of Indian Standards or BIS specifications for drinking water go back to 1983, when they were announced and are abbreviated as BIS-10500-1991.

The BIS adopted this standard primarily with the following objectives:

- To assess the quality of water resources

- To check the effectiveness of water treatment and supply by the concerned authorities

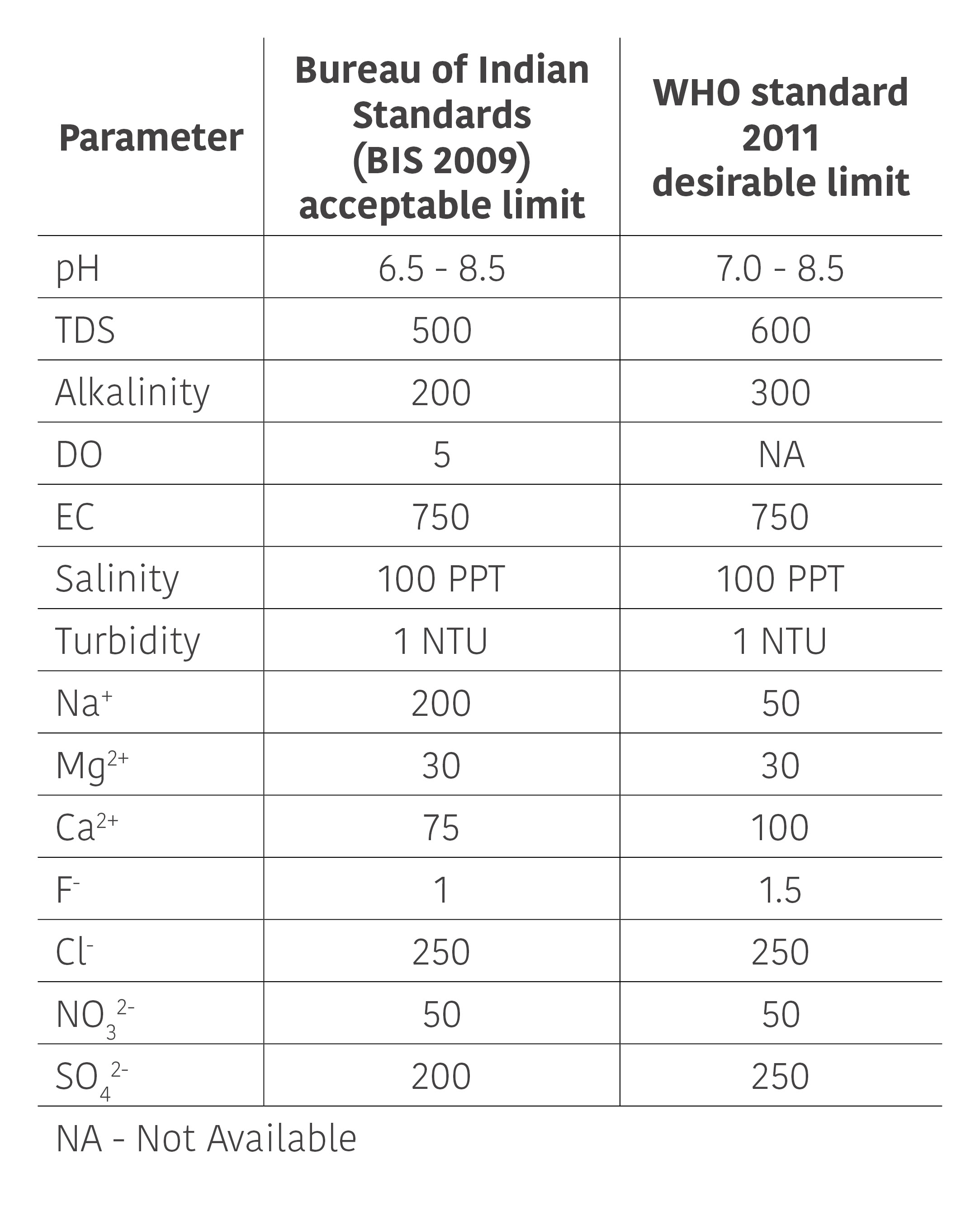

Criteria for Water assessment

Currently, the BIS standards for drinking water are not mandatory but voluntary in nature. Besides, in several instances, it is up to the supply authority’s discretion to overlook some of the attributes and ensure that the water supplied is safe.

The survey is being carried out in phases.

- First phase: 11 locations across Delhi

- Second phase: 10 samples from 10 locations of 20 state capitals

- Third phase: all North-East state capitals and 100 smart cities

Is BIS standards the only way forward? Water experts caution against the uniform standardisation of water across the country. Agro-ecological zones vary significantly throughout and a person in the plains may consume different pH water whilst someone in the hills may have access to good water that measures to another set of parameters.

How can this gaping difference between homes that have access to safe, potable water and those who don’t, be addressed? A possible solution could be to decentralise initiatives and urge local communities to take part in finding their own water solutions.

Alternative solutions

In the past, this has helped transform traditionally water-starved areas by bringing a collective group of citizens together to create their own supply.

A World Bank report states the example of around 5000 habitations building their own supplies in Uttarakhand in 2015 and transforming the lives of 1.5 million rural residents.

With unique challenges in every geographic and cultural district, the support of local residents may be the best way forward. The flip side to imposing a uniform standard may pave the way for unruly corporatisation of a living being’s most fundamental need. An optimistic outlook might be to enforce supplying agencies to conform to a minimum requirement of safety.